Welcome back for the thrilling conclusion of “Yeast Shepherding”. In parts 1 and 2, we’ve taken you on a philosophical journey explaining our impetus for and approach to collecting wild yeasts. Here, I’ll explain precisely how we get these yeasts and bend them to our will (or not). This is the story of how we take wild, untamed single-celled fungi and teach them the elocution of beer-making.

Nomadic Saccharomyces can be found in various crevices within the natural and unnatural worlds. Some say they have a preference for oak trees or fruit skins. However, we have managed to find these microbes on all sorts of surfaces. As I mentioned in the previous post, we think of yeasts as opportunists, spreading themselves scantly over the Earth’s surfaces. In this way, they ensure that they are always in the right place at the right time, kind of like Batman. So we set out to find them by swabbing surfaces that inspire us, in hopes that we’ll hit the fermentative jackpot. In one case, we went to the top of a fire tower in Middlesex Fells and held up a petri dish to the wind. In another case, we had lab guru Randy grab swabs of some cool plants he found in Florida. All of these yield potential new brewing candidates.

We typically collect the yeasts with swabs, and then feed them wort. Sometimes we drop them into liquid wort, other times we plate them on petri dishes. A key difference between these two options is that in a liquid, we aren’t able to separate any different species that we collect. We may be allowing one species to become enriched in this vial of wort, and therefore, we lose the chance to isolate the more sheepish creature. On a petri dish, each individual organism is separated on the agar and should be able to grow into a colony, so long as it is tolerant of the conditions we’ve provided. It also needs to be able to digest the sugars we’ve given it. Usually, we grow these yeasts on sugars that are representative of what you’d find in wort. If they can’t handle these, they won’t be able to make beer.

Once we’ve purified the microbes, we start to check them out microscopically. Do they look like yeasts? Are they budding? Filamentous? It’s nice to get a sense for what these microbes might be. Next, we want to see if these yeasts can handle the rigors of the brewing world. Can they tolerate hops? Alcohol? Do they stay suspended or do they drop to the bottom of the flask? These tests are critical to weed out species and strains that might never work in an industrial brewing environment. A yeast needs to be more than just a tasty fermenter to make good beer. It needs to have the right behavioral properties as well for it to be viable. For our wind-borne strain, dubbed ABC3, we found that it behaved remarkably well, completing vigorous fermentations after a few generations in culture, flocculating (or clumping) well after fermentation was complete, and tolerating hops and alcohol reasonably well.

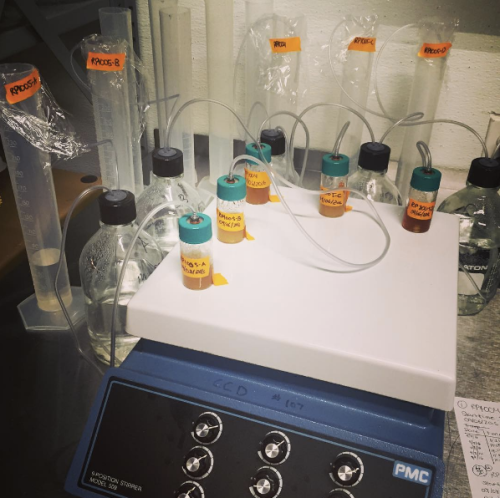

After our first few rounds of developing wild yeasts, it became clear that we would want to be able to quickly eliminate strains that wouldn’t work. We’ve developed a rapid screening process that allows us to perform lots of mini fermentations in parallel and monitor their progress in real time. We call this device the Fermenator. We use it to ferment tiny batches of beer and collect the CO2 from each fermentation to get real-time measurements of fermentation activity and progress. This allows us to choose strains that will perform well in our beers and get to the next steps sooner.

Once we’ve screened the yeasts for all of these properties, we can start getting to the exciting bits where we get to smell and taste things. This sensory analysis part is really why we do this. Do they smell like pineapples? Taste like leather? All yeasts are interesting until proven otherwise. We give them some leeway in terms of their performance versus what their potential might be. We believe that some strains may be coaxed to perform better or even taste better using some selective breeding techniques or even just changing fermentation conditions. Therefore, we try not to eliminate too many yeasts too quickly. Getting back to our ABC3 example, we let it run through a few rounds of fermentation and selected the top fermenters and bottom fermenters, choosing to propagate those that performed better in our trials. Ultimately, we liked its wild, fruity and spicy aromatics, plus it fermented pretty reliably, so we kept it going.

Once we’ve screened the yeasts for all of these properties, we can start getting to the exciting bits where we get to smell and taste things. This sensory analysis part is really why we do this. Do they smell like pineapples? Taste like leather? All yeasts are interesting until proven otherwise. We give them some leeway in terms of their performance versus what their potential might be. We believe that some strains may be coaxed to perform better or even taste better using some selective breeding techniques or even just changing fermentation conditions. Therefore, we try not to eliminate too many yeasts too quickly. Getting back to our ABC3 example, we let it run through a few rounds of fermentation and selected the top fermenters and bottom fermenters, choosing to propagate those that performed better in our trials. Ultimately, we liked its wild, fruity and spicy aromatics, plus it fermented pretty reliably, so we kept it going.

When a yeast shows real potential for brewing, that’s when we add it to our library and start to make recipes with it. When I take people on tours of our lab, I’m often asked how we choose yeasts to pair with our recipes. With wild yeasts, we typically do the reverse–we try to let the yeasts express themselves, and choose recipes that best feature the yeast. If, after a few rounds of testing, the beer tastes good, then the yeast is ready for prime time. For ABC3, we thought it had a spiciness and a hint of clove that would work well in either a wheat beer or a Belgian-style dubbel. Ultimately, it was the dubbel that proved to be our favorite.

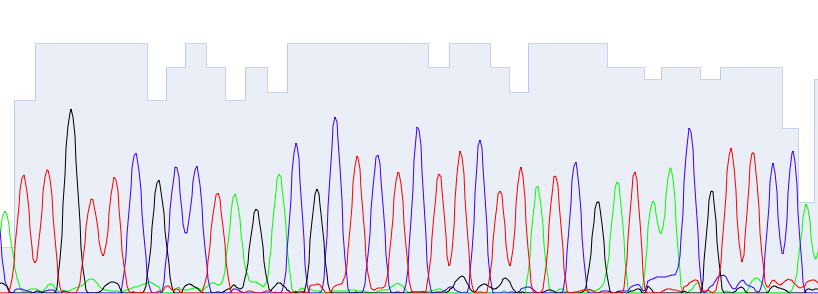

Typically at this point, we want to know what kind of yeast we are actually working with. Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Kluyveromyces? Something totally different? In our lab, we use some quick DNA sequencing methods to determine what genus and species we are working with.

By cross-referencing our sequences with public databases, we can identify these species and catalog them. We sequenced ABC3 and determined that it was most likely Saccharomyces paradoxus, a relative of our standard brewing yeast. Because we were ready to take this yeast to the next level, and because at this point, the one wild cell that we captured had produced so many offspring in our lab, we named ABC3 “Genghis Khan”, like the fecund warlord.

Now that we’ve officially immortalized ABC3 by giving it a name and cryopreserving it, we can consider it part of our brewery yeast family. We now brew the Genghis Khan Dubbel seasonally and offer it up in our taproom. It’s a great way to taste a truly wild yeast and get to know our local microbial terroir.

Of course, our exploration of wild yeast will not end with Genghis. There are many more interesting strains and species out there waiting to be found. So we beat on, swabbing and plating ceaselessly into the future. The nature of this search means that we’ll discard dozens of new isolates for every one strain that is promising for actual beer-making. To really understand a yeast strain and what it’s capable of, we must brew with it over and over again, documenting everything. We must give these strains different grains and sugar profiles, ferment with them at different temperatures, and provide them with opportunities to flex their metabolic muscles. We must get to know them. That part takes years. So join us on our journey as we continue shepherding yeasts from the wilds of nature to our welcoming taproom.